The worst butcher shop in the world

Once upon a time, there was a butcher shop. It was terrible.

What made it so bad? This butcher shop only used one tool: a meat grinder.

Typical butcher shops sell different cuts of beef: ribeye, filet mignon, flank steak, picanha, etc.

But this butcher shop only had a meat grinder. So they'd send entire cows through the grinder — bones, organs, and all — and sell the result as "beef paste." Instead of butchering pigs into chops, tenderloin, bacon, and ham, they'd grind up whole pigs and sell it as "pork paste." They did the same with chicken, turkey, and every other type of meat they sold.

One day, a new customer entered the butcher shop. "I'll take two bone-in ribeyes please," they ordered.

"Sorry, we don't sell steak," the butcher replied. "But we do have beef paste. And it's a very good price. How much would you like?"

"I was really hoping for ribeye," the customer said. "I don't mind paying for quality meat. Could you just go in the back and cut me a few steaks, please?"

"Sorry, no," the butcher replied. "But our beef paste does contain ribeye!"

"It contains ribeye? How much ribeye? And what else is in there?" asked the customer. "Are there hooves? I'd prefer not to eat hooves."

"We use every part of the animal!" replied the butcher, enthusiastically.

Understandably, the customer left the store without buying anything.

🥩

Product segmentation

My fictional butcher shop is unrealistic. And gross. But it's also a decent metaphor for the current homogeneity of podcast ad inventory. Consider, for example:

Not all airplane fares are the same. Business class costs more than economy.

Not all clothing is priced the same. A t-shirt made from pima cotton costs more than one made from a cotton-polyester blend.

Not all TV advertising is priced the same. Super Bowl ads costs more than FAST channel ads.

This isn't an unusual concept: different products for different people at different prices.

But strangely, the status quo in podcasting means selling big buckets of mostly undifferentiated ad "impressions." And like the butcher shop's beef paste, it's not clear exactly what's in those buckets of impressions.

A few months ago, I spoke with someone from a medium-sized podcast network that publishes video episodes on YouTube and audio episodes through RSS feeds. Both audio and video episodes contain so-called "baked in" ads, which are sold on a CPM (cost per thousand) basis.

I asked how they calculate ad impressions. The answer was simple: "We add up YouTube views and RSS downloads."

I asked how video impressions were priced compared to audio impressions. Again, the answer was simple: "We use the same CPM across audio and video."

To me, this isn't much different than grinding up an entire cow and selling it as beef paste. And for both sides of the marketplace, buyers and sellers, this seems ridiculous. Especially if, like me, you know that...

Podcast ad "impressions" are not all equally valuable

Here at Bumper, we buy a lot of podcast ads. If you promise not to tell anyone, I'll let you in on a media buying secret: the best-performing ads we buy are the ones that people actually see and hear.

Ads that get played are worth more to us than ads that don't.

It can be remarkably easy to buy podcast ads that never get heard. My phone is full of automatically-downloaded audio files that I will likely never play. Those downloads contain advertisements (some baked-in, some dynamically inserted) that I will probably never hear. Somebody somewhere paid for those ad impressions, and for their sake, I hope (a) they know that many delivered ad impressions never get played and (b) they're upset about this.

In the traditional CPM-based podcast ad sales model, where ad impressions are inserted into podcast downloads, advertisers pay the exact same amount per ad impression, regardless of whether anyone actually hears their ad. That seems absurd.

Moreover, in the world of video podcasting, we've learned that video retention rates and average view durations are typically much lower than their audio episode counterparts. Almost always, far more people start an episode (and trigger a "view") than actually make it to any mid-roll ad break.

I've run the numbers on many shows, both audio and video, and found the following:

There's usually a big difference between the number of ad impressions delivered, and the number of ad impressions that have demonstrably been played back

The ratio of ad impressions delivered vs. ads actually consumed varies from show to show, episode to episode, and platform to platform

Platform-specific details matter a lot. For example, an audio ad within a download delivered to a Spotify user has a much higher chance of being played than the same ad within a download delivered to an Apple Podcasts user. Why? Because of Apple Podcasts automatic downloads.

If I had the choice, Bumper would only buy podcast ads that actually get seen or heard. Who wouldn't? And like the customer at the butcher shop who wants to buy ribeye steaks, I'm willing to pay a premium for ads that have a high likelihood of being played.

Unfortunately, most of what's available from podcast networks is the podcast ad equivalent of beef paste. Sure, some of the ad impressions I buy will actually get heard. But to get those "good" ad impressions, I also have to buy an unspecified number of ad impressions inserted into downloads that will never be heard by anybody.

I wish more podcast networks would just let me buy ribeye.

And the thing is, they could.

Verified impressions

Bumper is actively working on a metric we call "verified impressions," and we've begun calculating this for our clients.

What's a "verified impression" in podcast advertising? Simple: it's an ad impression that actually gets heard or seen, backed up by first-party data from podcast consumption platforms.

This distinction only becomes meaningful once you realize most ad impressions sold by podcast sales teams aren't guaranteed to be heard. For example, when the Apple Podcasts app on my phone automatically downloads a new episode of an ad-supported podcast, any ad impressions sold into that episode are "delivered" at the time of download, regardless of whether I actually play the downloaded file.

Some ads get played. Others don't. And it's not easy for advertisers to know how many of each they're buying.

Verified impressions, on the other hand, are backed up by first-party data from platforms like Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and YouTube. All three platforms report on actual podcast consumption, unique users, and episode-specific retention. This lets us scale episodic retention curves by audience size and stack them on top of each other:

Suddenly, we can clearly see the number of people present at any given ad break. See the "ice cream scoops?" That's ad avoidance, and everything under that point on the graph is what we mean by "verified impression." It's the number of times a person was present during playback of an ad.

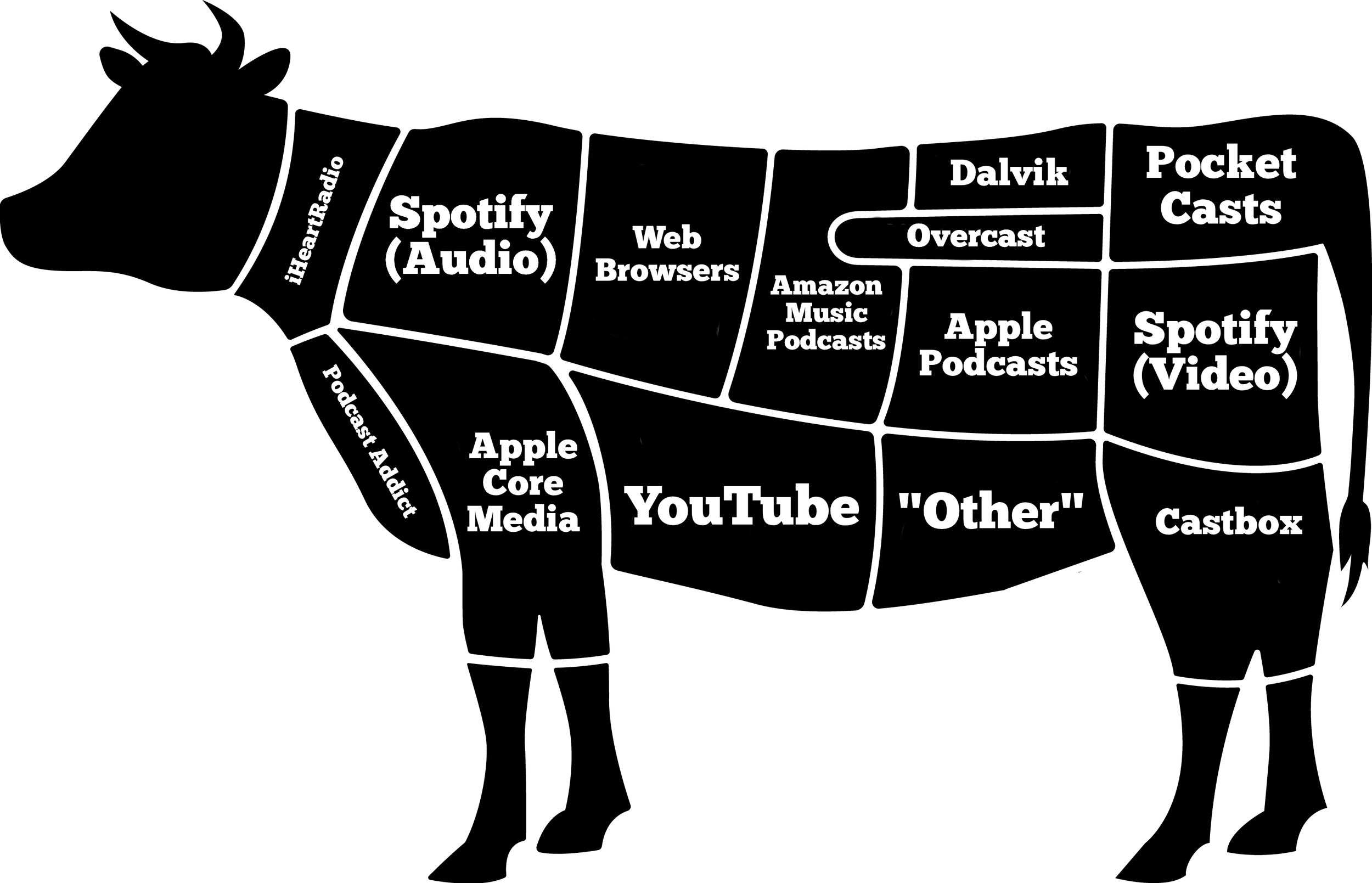

"But Dan!" you might be shouting. "That's just YouTube, Apple, and Spotify! What about all the listeners who use Overcast, and Pocket Casts, and Castbox, and Google Chrome, and this thing called AppleCoreMedia? I still want to sell ad inventory inserted into those downloads."

The bad news is that many podcast apps don't report consumption data back to publishers, so they can't be included in "verified impressions."

But the good news is...

You don't need to choose

When it comes to podcast ad inventory, verified impressions aren't a direct replacement for the download-derived legacy "impressions" that sales teams have been selling for years. It's not an either/or choice. Rather, verified impressions represent an opportunity for product segmentation. Verified impressions are the ribeye. Everything else is meat paste.

And like a good butcher shop, you can sell both, and charge more for the good stuff.

Like I said, Bumper buys a lot of podcast ads for our clients. If a podcast ad vendor offered me the opportunity to only buy verified impressions — ads that were provably listened to — I'd jump at the opportunity. And I'd pay a premium, because I know the conversion rate on ads that don't get played: zero.

Airlines sell business-class fares and economy fares.

Butchers sell ribeye and soup bones.

Clothing storie sell high-end fashions and more affordable options.

Some brands advertise during the Super Bowl and on FAST channels.

I believe podcasters can and should sell verified impressions (at a premium price), and also sell legacy download-based "impressions." Both have their place.

Are you grinding up entire cows? Do you know how much ribeye is in your meat paste? Interested in verified impressions? Get in touch.